Necessitous Versus Symbolic Labor

The meaning of work in an age of automation, from CNC sculptures to AI data centers

The other day I stumbled upon this video of a machine carving a beautiful statue of St. Joseph:

Some people in the comments section expressed their discontent concerning the means employed in crafting these sculptures:

Micah was not happy:

Joeseph wasn’t the only one to feel a bit let down:

Is Micah right to be annoyed? Are Joeseph and Seria correct in their cynicism and sadness?

There’s a point I want to make here about the symbolism of behind our labor. But before I do that, I have one more example.

Wyoming’s CNC Monastery

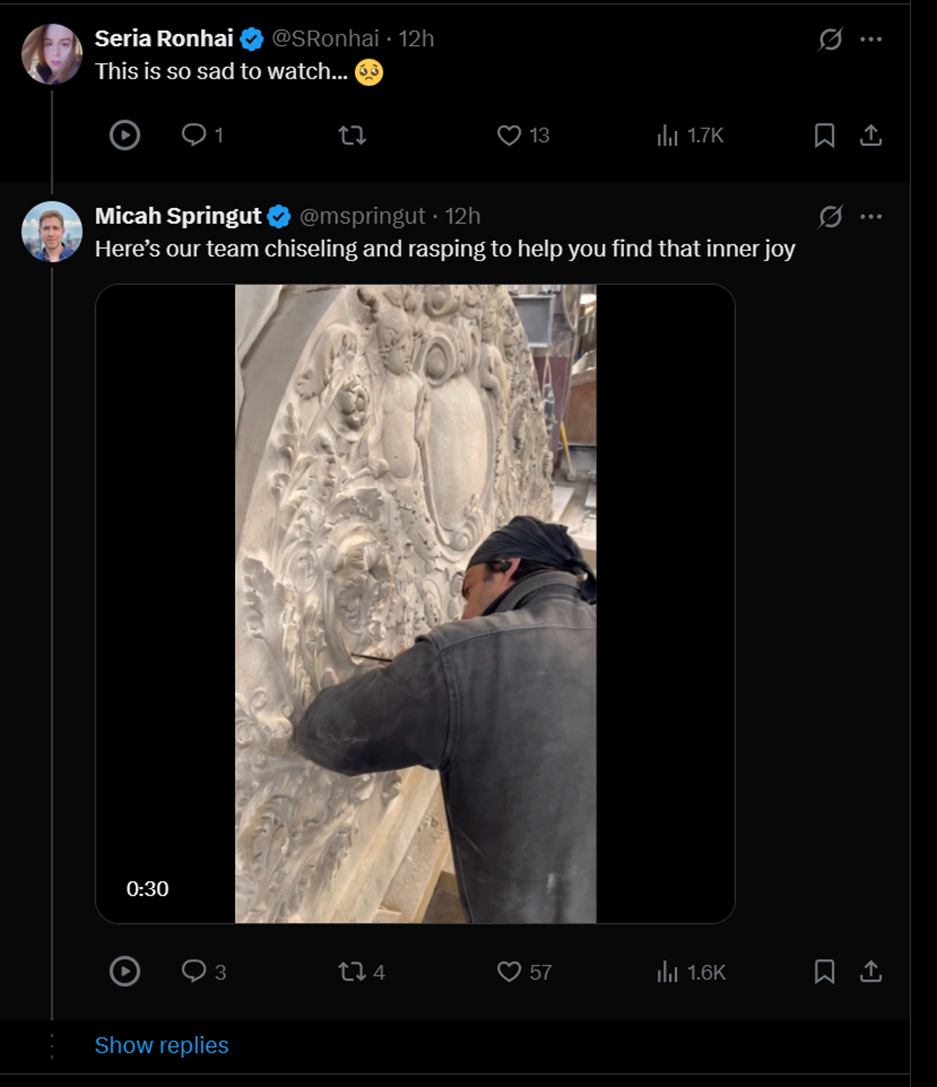

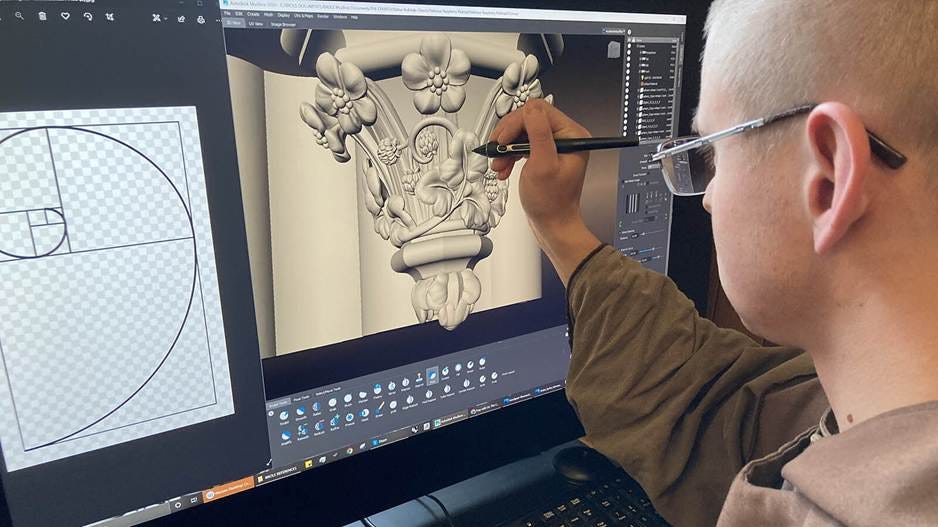

A bunch of Carmelites in Wyoming are building a monastery in the Gothic style.

It is a thing of beauty, especially given its splendid mountain setting.

Like something out of A Canticle for Leibowitz, they’re using CNC machines to help carve the stone and to complete some of its features.

When the brothers learned it would still cost $80 million to finish the project, they realized they needed some way of cutting costs. Brother Isidore Mary explains,

And when we were looking at the quotes, the biggest line item was always the stonework. So we said to ourselves, “Well, carving the stone can’t be that difficult. Why don’t we just learn to carve the stone ourselves? And that will take care of most of the cost.”

To be clear, I am grateful that they’re building a Gothic monastery, especially in such a picturesque setting as Wyoming. I don’t have a better answer to their $80 million problem.

Yet, we still need to ask a few questions.

Why would some people have one reaction when they see the Gothic monastery (depending on their orientation, everything from joy to gratitude to being impressed) and quite another once they learn how it has been made (let down, less impressed, sad)?

Or, in the very least, why might some people feel conflicted about this CNC monastery?

Necessitous Versus Symbolic Labor

The reason I think people feel conflicted by having a machine do the sculpting is because of the symbolic dimension of work.

A brief digression on human motivation is in order.

You can make sense of a man’s actions in all sorts of different ways. You can use psychology to try to understand why an assassin would etch a certain message into his bullet casings after murdering a CEO or public figure. You could use economics or sociology to do likewise.

But symbolism itself can serve as a motive for human action.

The man’s killing and his bullet casings themselves are symbolic. His victim and his manifesto were chosen for a (symbolic) reason. The Twin Towers stood for something. Removing another’s cranium, as jihadists are wont to do every now and then, likewise means something, just as removing the head of an organization after a major crisis or sports team means something.

All iconoclasm is symbolic in nature.

This brings us to the symbolism behind sculpting something out of stone.

In his Permanence and Change (henceforth P&C), written just after the Great Depression, literary critic and rhetorician Kenneth Burke distinguished between what he called necessitous labor and symbolic labor.

It is one thing to climb a mountain to get somewhere. It is quite another thing to climb that mountain for the sake of climbing it.

Burke writes,

We might make a distinction between necessitous and symbolic labor by suggesting that drudgery is purely necessitous labor, whereas symbolic labor is fitted into the deepest lying patterns of the individual. Symbolic labor is more pious. For instance, it would be ‘necessitous labor’ if one climbed a mountain simply because he had to get somewhere and the mountain stood between him and his destination. The same act would be symbolic if the mountain happened to have some deeper significance to the climber, so that the act of climbing was in itself an accomplishment. If one has ever read the experiences of a confirmed Alpinist, he will appreciate the difference, for in the case of the alpinist the incidental dangers are not merely endured, they are courted. (P&C 82)

The magician, stuntman, and performer David Blaine is a great example of a man who does not merely endure dangers but courts them.

If the goal is just to simply create a Gothic sculpture, then the means to that end do not really matter. But Burke would remind us that the means themselves do matter since they have symbolic significance.

Per William Rueckert, a commentator on Burke’s work, hobbies are a great example of symbolic labor. We do not pick up hobbies out of necessity. The weekend warrior cutting wood in his garage with his father’s old power tools is doing something more than sawing lumber and gluing it together. He’s making an altar with all the piety and devotion he can muster.

This distinction between necessitous and symbolic labor helps us to better understand the meaning of a difficult task—whatever that may be, whether lifting weights or being buried up to your neck and having fire ants climb all over your face (as the case may be in some indigenous puberty rites). Say what you want about the relative uselessness of having a student write a ten-page essay paper. But it is a rite of passage, for better or for worse. And the meaning of that writing is what we lose when we have a machine do it for us.

Im(piety) and the Technological Psychosis

“Piety” is another one of Burke’s key terms. Carving a stone sculpture with a machine feels like an act of impiety because of our sense of what goes with what. Stone signifies difficulty (in addition to permanence). To make the traditionally difficult easy is to commit an act of impiety (in Burke’s sense of the term).

We should not necessarily esteem something merely because it is difficult, of course, as I believe Aquinas reminds us somewhere. But oftentimes we do because of what that difficulty means. There’s a reason the Guiness Book of World Records exists. It is a catalogue our many symbols of difficulty. In many ways, the Guinness Book is a testament and ode to Difficulty.

The utilitarian philosophy of our era (as of Burke’s) hinders us from recognizing the symbolic dimension behind actions. Burke calls this emphasis on means (or uses) over ends the technological psychosis. He doesn’t call it scientism or experimentalism or secularization. But these terms point in the same direction. Here’s Burke:

Though it is customarily traced back to the Copernican astronomy, Galilean physics, and the Baconian rationalization of the inductive method, the [technological] psychosis cannot be said to have fully blossomed until the time of the Utilitarian philosophers in England, the first country to feel the full shock of systematic technological development. The doctrine of use, as the prime mover of judgments, formally established the secular as the point of reference by which to consider questions of valuation. (P&C 44-45)

Burke identifies Darwin as “within the spirit of this psychosis when discussing the development of moral and intellectual traits as tools or weapons in the struggle for existence” (P&C 45). In other words, a man believes this, that, or the other thing because it is useful (to the propagation of his genes, for his fitting into a particular niche, for simply surviving, etc.). We can always discount a man’s argument or belief system by saying that it merely serves his interests, because it is useful to him (P&C 45).

Nowadays, the technological psychosis provides the rationale for choosing this degree over that one. What matters is that the degree is useful.

A man uses a machine to make stone sculptures because it is useful.

The utilitarian emphasis on use (or utility) confuses the significance of means in relation to ends.

Burke gives the example of classifying a lion, traditionally a masculine symbol signifying honor, power, and kingship. Despite these symbolic connotations, it may be more useful for the biologist to classify the lion as a feline (a cat), traditionally a feminine symbol.

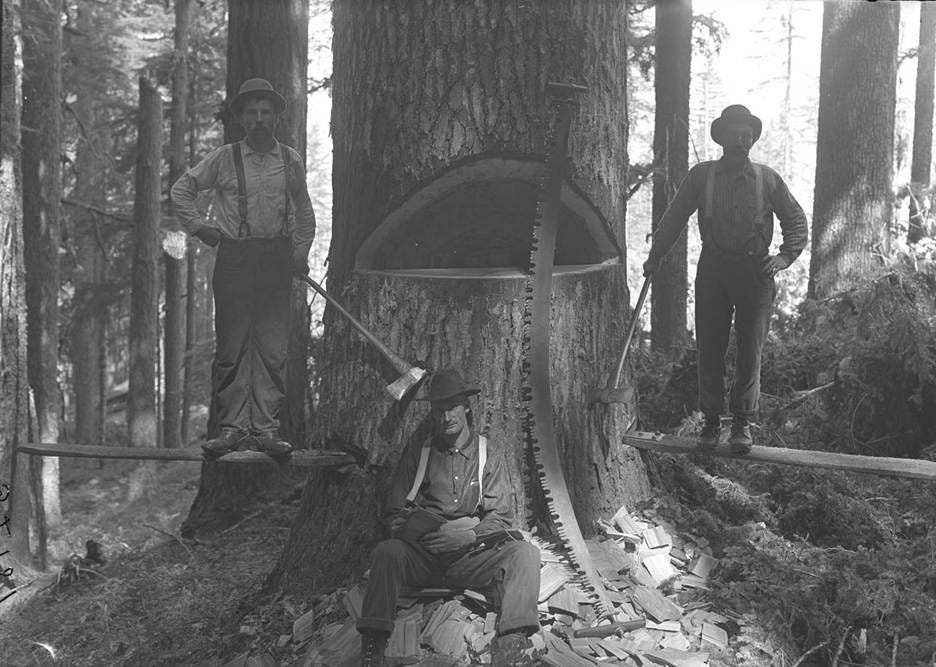

Burke also discusses cutting down a large tree. The technological psychosis would have us disregard what that tree means or stands for.

It is possible that much of the anguish affecting poets in the modern world is due to the many symbolic outrages which a purely utilitarian philosophy of action requires us to commit. In primitive eras, when the utilitarian processes were considerably fewer, and more common to the entire group, definite propitiatory rituals seem to have arisen as a way of cancelling off these symbolic offenses. In the magical orientation (so close to that of poetry) if the felling of a tree had connotations of symbolic parricide, the group would probably develop a corresponding ritual of symbolic expiation. The offender would thus have a technique for cleansing himself of the sin he had committed. (P&C 72)

Burke continues,

The purely utilitarian attitude toward such acts, however, requires that one introduce a distinctly impious note: one cannot permit the symbolic overtones of meaning to function at all. If the tree falls, and one feels a strange uneasiness, one must shut off the queer remorse by an impatient ‘Nonsense! –this is only one tree, I needed it, and there are plenty of others to take its place.’ The non-utilitarian attitudes of the act are dismissed—one must perform the act as a ‘new man’—and when the great oak falls, only the poet, bewildered and plaintive, may permit himself to feel that there is somehow a deeper issue here than the mere getting of firewood. (P&C 72)

If we feel a “strange uneasiness” at a machine carving St. Joseph, we might simply dismiss it as nonsense. But Burke would invite us to listen to that odd feeling, to try to discern why we feel the way we do at such an act.

Utilitarianism (the technological psychosis with its emphasis on use above all else) commits acts of symbolic impiety. It shaves off the transcendent dimension that always attends our actions, leaving only the immanent (and useful) behind.

What is more is that such acts of impiety against the symbolic order can be felt as painful and therefore require “symbolic expiations … to counteract the symbolic offenses involved in purely utilitarian actions” (P&C 74). That symbolic expiation, Burke would suggest, is what a poet does when he or she writes poetry.

If some local utilitarians decided to cut down a great tree for economic purposes, one should expect the resident poet to take up his or her pen. Or, in the very least, that sad sap Romantic painter would have a new subject for a landscape. Or the melancholy songwriter would at last have a theme for a ballad. As Johnny Cash would sing in “Paradise,”

Daddy won’t you take me back to Muhlenberg County

Down by the green river where paradise lay?

I’m sorry, my son, but you’re too late in asking

Mister Peabody’s coal train done hauled it away

Well, the coal companies came with the world’s largest shovel

They tortured the timber and stripped all the land

They dug for the coal till the land was forsaken

Then wrote it all down to the progress of man

Oh, daddy won’t you take me back to Muhlenberg County

Down by the green river where paradise lay?

I’m sorry, my son, but you’re too late in asking

Mister Peabody’s coal train done hauled it away

Automation and the Future

Why does all this matter?

These considerations about the symbolic dimension of work will only become more important as automation takes hold in our hypnotized age. I think we’re in an AI bubble right now. There’s an extraordinary amount of hype and snake oil being sold to the public.

Nevertheless, many are predicting that many trees will need to be cut down in order to make way for our AI utopia. And by “trees cut down” I mean “workers fired” and “reservoirs drained” (both financial and aqueous) in addition to actual trees cut down.

Our technocrats do not possess the requisite vocabulary for making sense of what this is going to do to people at the symbolic level. We have some foreshadowing of what to expect. We’ve seen how some react to stone sculptures made with machines (and how others might write these reactions off).

Let us conclude.

Why did the chicken cross the road? From the perspective of necessitous labor, crossing the road was simply a means to an end (i.e., the other side). But when it comes to symbolic labor, the chicken crossed the road because it was the most dangerous and difficult road he could find. Plus, all the other chickens were watching, including Roosty McRooster, who just the other week had crossed an eight-laner blindfolded.

Why did the technocrats build the gigantic leech of a datacenter in the middle of Texas? From the perspective of necessitous labor, it was simply a means to an end (i.e., the God of Compute, the Silver Bullet in the Trade War). But as it pertains to the symbolic dimension of this act, it was because it was the most expensive and daring thing they could dream up. Plus, all the other countries were watching, including China.

The more terrifying consequence of Burke’s observations is that the building of gigantic data centers (much like the building of gigantic atomic bombs) will itself take on symbolic significance for those involved. Deprive the world of the symbolic dimension and the non-utilitarian, if you insist. But prepare yourself for men to write their poems by other means.

Justin Bonanno is an Assistant Professor and student of rhetoric. He’s currently reading Kenneth Burke, Alasdair MacIntyre, and Scott Meikle. For more on the symbolism of human action (and symbolism as motive), see the work of Kenneth Burke and Hugh Dalziel Duncan.

This is very good stuff Justin. I'm going to have to read P&C.

You should send this to Kingsnorth or his Substack if possible. I think he'd find it very interesting.