Neil Gaiman on the Art of Storytelling: Part II

How to get (and keep) a story moving; thoughts on character, dialogue, and plot

So, my wife and I finished (for the most part) Neil Gaiman’s MasterClass on the art of storytelling. It really was worthwhile.

Last week, I talked about some of Gaiman’s ideas related to finding ideas for stories and beginning to develop them. In today’s post, I’ll offer a few gems and metaphors related to character, dialogue, and plot.

Since there’s quite a bit to cover, I’ll do my best to touch on some of the highlights. I’ll also try to throw in some of my own examples to help illustrate Gaiman’s points. Next week, I’ll do one last article on Gaiman’s MasterClass.

Get Moving: “What if?” and Funny Hats

Much of what Gaiman says concerns how to get moving and how to stay moving when you’re writing. As I noted in Part I, you have to have an idea to develop in the first place. The idea is like the germ or the seed that the story grows out of, and it can begin with the question “What if?”

I wrote about the importance of asking this question in last week’s post, but since it is so important, I wanted to include it here again. Consider the following “What if?” scenarios:

What if an alienated weatherman was doomed to live the same day over and over again until he got it right (Groundhog Day)?

What if you could share dreams with other people and plant ideas in their head a la a reverse heist (Inception)?

What would happen if a person’s entire life from conception to death were made into a reality TV show (The Truman Show)?

Note that Groundhog Day, Inception, and The Truman Show are all original screenplays—not adaptations. The “what if” is a powerful stimulant and lightning rod to get your Frankenstein up off the table.

If you have a “what if?” (and even if you don’t have it), you can begin to play with character. Now, I don’t think Gaiman says as much, but the spirit of play seems to pervade his whole approach to writing stories. You have to play around a bit. You have to mess with the characters and their world. If you’re too caught up in a mechanical approach to writing (or doing whatever “they” tell you to do, as it pertains to writing), you’re probably going to write something stiff and uninteresting.

You have to play. You must play. Play, play, play.

Perhaps one of the most important things you can do to get the game going and to start messing around is to begin with character wants and needs.

What does Bill Murray’s character want in Groundhog Day? Well, perhaps at first he wants to get in and get out of Punxsutawney. He’s cynical and selfish. As the movie progresses, he wants to get out of his nightmare of having to live the same day over and over again. This desire drives his actions as he attempts to find a way out of the cyclical loop he’s found himself in. But what does he need? He needs to stop being so egotistical. He needs to be more selfless. The theme of the whole movie follows from these wants and needs, and it is essentially this: Die to yourself.

Asking yourself what your character wants or needs is a way of getting yourself unstuck as you write. You’ll hit a wall at some point, and then you have to ask: What does so and so want?

How else do you play with character?

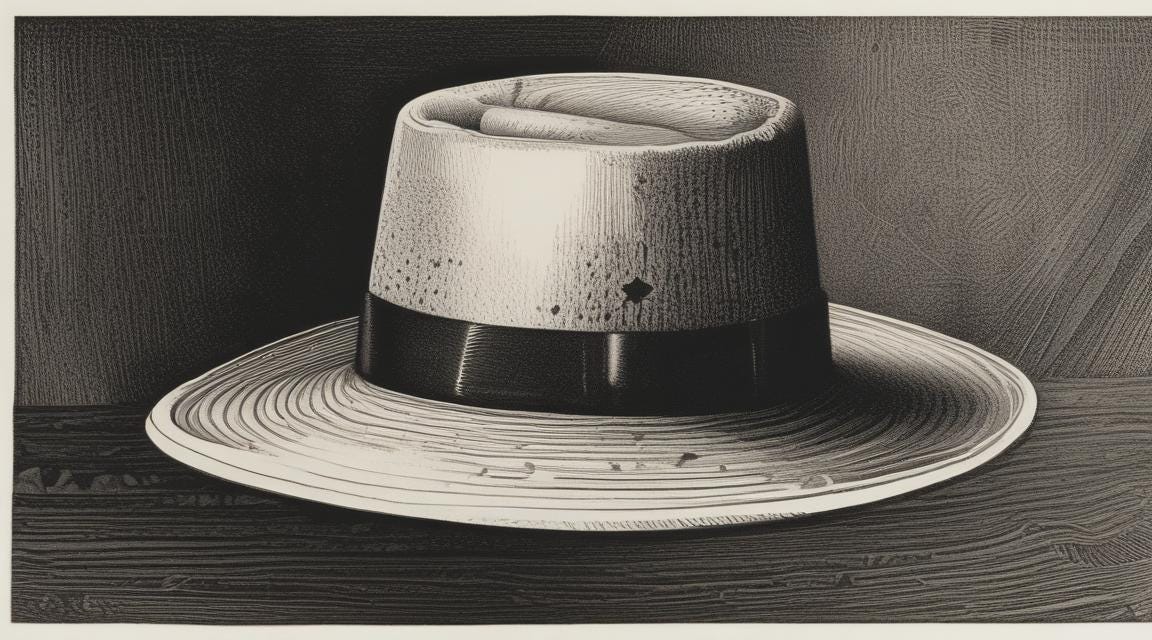

Well, for one, you can give them what Gaiman calls funny hats, which are those things that differentiate them from other characters. Ned Ryerson in Groundhog Day has a nasally voice, trench coat, briefcase, and huge glasses. He’s a living cliché of the person you somewhat knew in high school or college who now wants to sell you insurance or financial planning. Superheroes, too, have “funny hats” that differentiate them from other characters so that the characters do not all appear the same. What is Mr. T without his golden chain and mohawk? They are living exaggerations. The question is: What do you want to exaggerate in a character so that he doesn’t blend in with the wallpaper of your story?

Dialogue itself could be a type of funny hat. Gaiman questions the strict division between dialogue and character. As he might say, dialogue is character. You know who your character is based upon how they speak and what they say. As Christ said, “For out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaketh.” Words reflect personhood perhaps better than anything else.

Think here of Planes, Trains, and Automobiles (another original screenplay). So much of the conflict and characterization comes through in the dialogic exchanges between Del and Neal. Some might instruct you to put together a detailed backstory on your character, but Gaiman eschews this advice. He simply wants to know how people talk.

Stay Moving: Plot

Once you’ve got a character or characters and a powerful “what if?,” you might have a vague idea of what will happen. Again, a character’s wants and needs drive the plot. But there’s also more to plot than simply that. You absolutely must have something opposing those desires, and you have to build resistance to those wants and desires into the plot.

What does Cobb want in Inception? He wants to get home to his children. But there’s another character powerfully opposing this want: Mal, Cobb’s deceased wife. She wants him. Saito, the Japanese businessman, also has a particular want: He desires to break up Robert Fischer’s empire.

The intersection and opposition of these wants creates conflict, and conflicting desires drive plot. If you have a character that wants something and nothing stands in his or her way, you’re probably going to write something boring.

If you run into an issue while writing your plot, as Gaiman would say, the issue is probably earlier in your writing. You should read your piece from the beginning to find out where you went wrong. Painful though it may be, you have to retrace your steps to try to find where you closed off a forking set of possibilities that you needed to explore.

The more that you write, the less possibilities for story development remain open for you. Each decision closes off other possibilities for the story. As Richard Thames used to say, at a certain point in time, the story simply writes itself because of the form inherent in what you’ve already written.

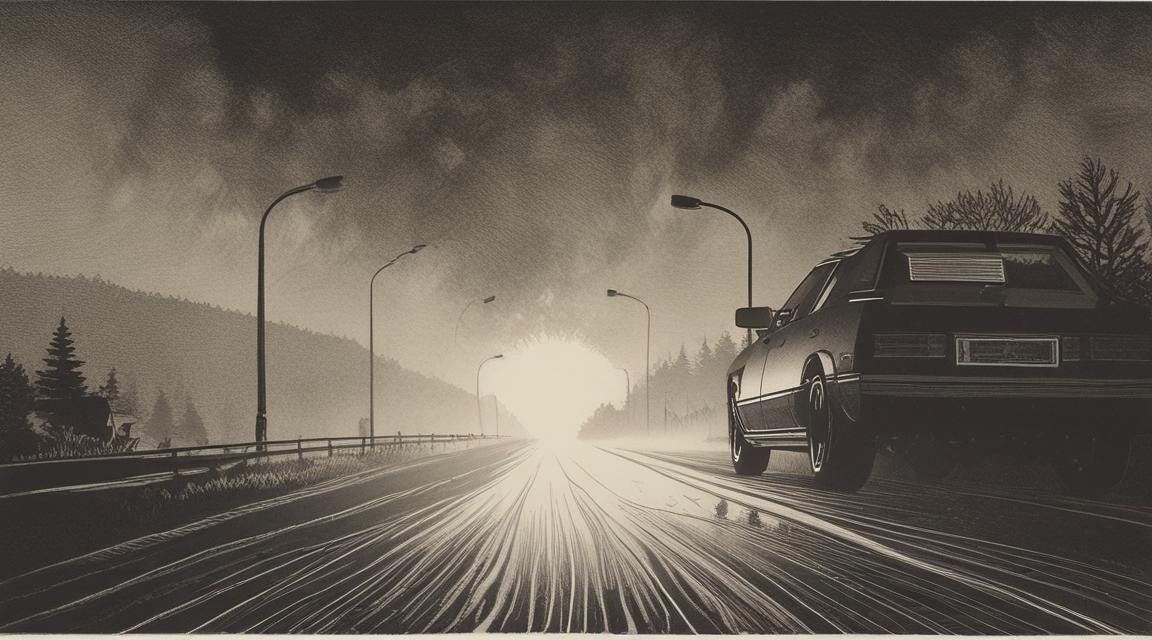

Gaimain likens writing a novel to driving in the fog with one headlight out. It’s all about forward motion, going slowly. Every now and then the mist will clear, and you’ll see a vista in the distance. Glorious. And then the fog will come back. Don’t panic.

Just write the next thing you know, and you’ll be fine. Don’t presuppose that you’ll know everything that will happen, even if you write from an outline. Being comfortable with not knowing what will happen keeps you in the game.

Thanks for reading, whomever you are. If you think others might find this interesting or thought-provoking, why not share it with them? And also, why not leave a comment or a question or a provocation below? A brief note on the comment above about about exaggeration. Somewhere, McLuhan talks about great art as a type of exaggeration (an exaggeration of form, in particular); he may mention this in From Cliché to Archetype.