Every Classroom Needs a Purpose

A defense of the liberal arts in response to Dr. Michael Martin

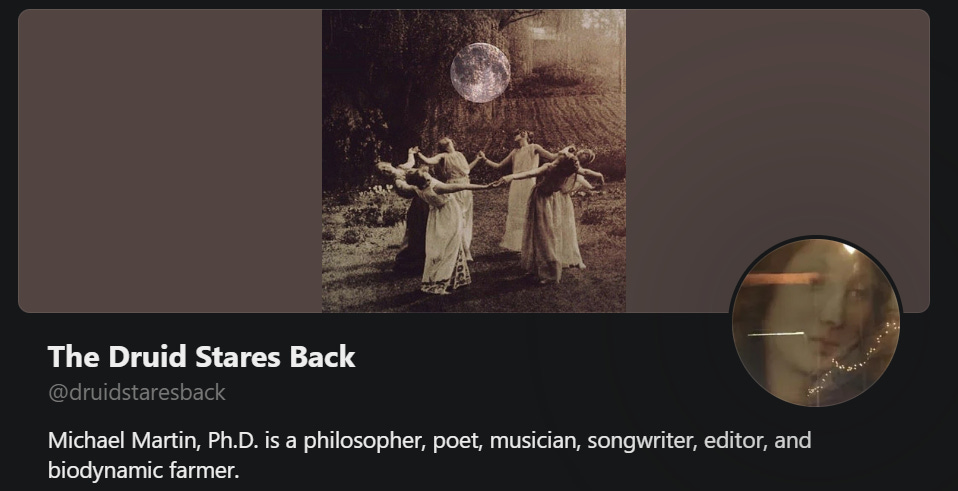

Back in July, Dr. Michael Martin wrote an article entitled “The Zombie Liberal Arts College Apocalypse,” a Substack piece about the inevitable death of liberal arts colleges. In today’s post I respond to Dr. Martin, aka The Druid Who Stares Back.

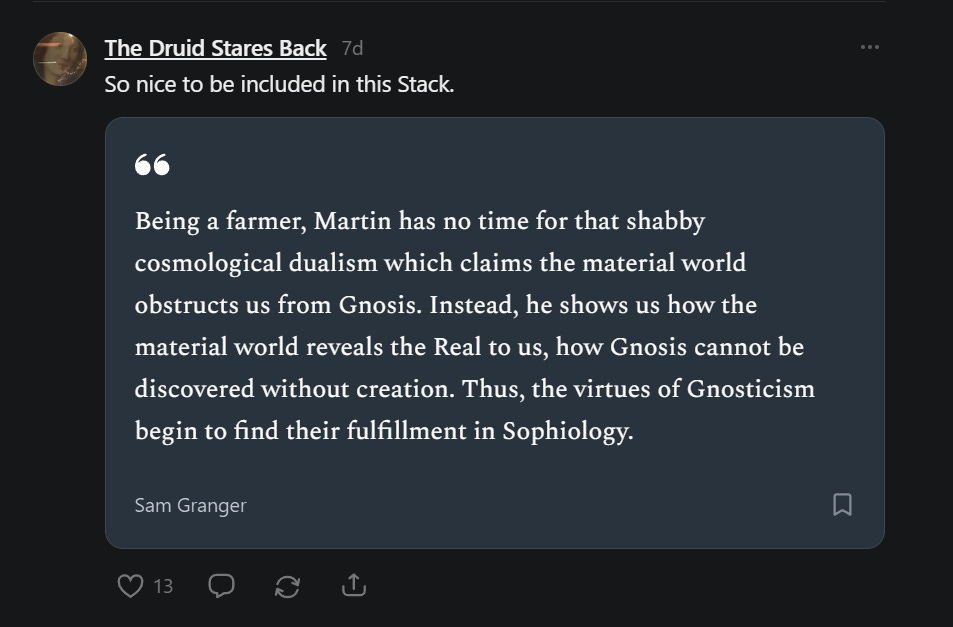

Martin is a former academic, farmer, “Sophiologist,” and maybe even a real, live Gnostic. I don’t know about that last one, so don’t quote me on it, but he did post this to his Substack Notes, an excerpt from this article by Sam Granger:

Martin was a former professor at two Catholic schools, Marygrove College and Siena University. The former is now out of operation, and the latter is slated to close at the end of the 25-26 Academic Year.

If he is a Gnostic and has been for quite some time, it makes you wonder how much Marygrove and Siena cared about their Catholic identity. Honestly, I’m not sure. Would that have anything to do with their demise?

In any case, there’s a great deal to sympathize with in Martin’s article. Indeed, as per Martin, there are Marxist and feminist maniacs who somehow get hired, receive tenure, and then proceed to torture students/colleagues with the most jargon-ridden, abstruse, hot garbage you could ever possibly imagine.

At an academic conference this summer, I watched a keynote speaker explain how “we” (whoever that is) formerly thought only men were persons, then we included women as persons, then we included deer as persons (I’m not kidding), and so—perhaps in the near future—we will include toasters as persons. I walked out of the room after this comment, so I’m not sure where this guy went with his toaster persons.

Everyone has to suffer through these peoples’ pontifications as they, in Martin’s words, “play professor.” It is obnoxious and soul crushing, especially if you’re a student who disagrees with what they’re saying. Moreover, I share Martin’s reservations about university e-sports (video game) programs as tactics to lure students to campus who have no business being there.

Thus, I would say, yes, good riddance to those who hijacked the liberal arts for their own purposes and with no care whatsoever for their students’ professional prospects and development as human beings made in the image and likeness of God.

But when it comes to his basic argument, Martin goes too far. He thinks that liberal arts colleges are dead. Technically, right now they’re the living dead, according to him. They’re zombies still admitting students and going about business as usual. Speaking in a prophetic tone, he writes:

“Since 2020, almost fifty liberal arts college in the US have closed, and this is a trend that will probably continue until only a prestigious few are left.”

And:

“The ecosystem of American higher education is in complete collapse. It will never recover.”

And:

“There is no fixing this.”

And:

“… the liberal arts college as we have known it is at its end. And this demise will surely afflict even the Harvards and Princetons of the realm. It’s a lab leak of a human-manufactured pathogen.”

“The jig, at long last, is up.”

I write what follows in a spirit of goodwill. My guess is Dr. Martin means well. But I’m not convinced the jig is up. The chickens will come home to roost for some institutions, perhaps even most, especially those that drifted from their initial mission and especially their religious identity in a bid for “free inquiry.”

But they key word is some—not all.

The Need for Narratives

Admittedly, institutions of higher education need money to keep going. Lots of it. But without a life-giving narrative, raising money (or paying for school, if you’re a student) is superfluous.

Nobody gives money to an institution they don’t believe in—let alone time or attention.

Interestingly, Neil Postman outlines the absolute necessity of narrative to education in his 1995 The End of Education. In this book, Postman doesn’t defend liberal arts, per se, since his concern is public education. Yet, much of what he says has merits for those seeking to defend the liberal arts.

Postman writes,

Without a narrative, life has no meaning. Without meaning, learning has no purpose. Without a purpose, schools are houses of detention, not attention. This is what my book is about.

Postman is simply reiterating what Nietzsche and Victor Frankl have already articulated: If you have a why, you can bear any how.

Unlike many, Postman realizes that educators must provide a rationale for what they’re doing. They must justify their practice. And they need to get used to doing so on a regular basis, especially since they face competing narratives that want them shut down, closed, terminated, etc.

Even though Postman published The End of Education thirty years ago, the strange gods (aka the counter narratives) he mentions still hold sway in disputes about the merits of the liberal arts. These counter narratives include, among others, the gods of Economic Utility, Consumership, and Technology.

False Gods (and Real Zombies)

These strange gods are the real zombies, not liberal arts colleges, per se. They come back year after year to assault the liberal arts and to lure students, faculty, and funds away.

They’re the living dead.

And they, too, are a human construction, “a lab leak of a human-manufactured pathogen,” to quote Martin again.

The god of Economic Utility is perhaps easiest to understand in the context of the liberal arts. It is the one that impresses parents and politicians most. If you do well in school, so the story goes, you will receive your reward: a job. As per Jane Jacobs, some view education as the credential that you need in order to board the train of the economy. It is a ticket to be punched.

In this particular narrative, you are your work.

Now, to be clear, I want my students to get good jobs, to find meaningful work, and to be able to provide for themselves and their families after graduation. A good liberal arts education can help students to do this. Absolutely. One highly successful business owner told me a few years ago that he preferred students with liberal arts degrees because they could perceive situations and problems more holistically than their more specialized and highly technical counterparts.

However, the god of Economic Utility does not give us a reason for going to school. Read that line again. It doesn’t. It does not fill us with a lasting purpose, and for this reason, many students do not believe in it.

The god of Economic Utility owes its prestige to its linkage with the god of Consumership, wherein you are what you can accumulate. For Postman, advertisements serve as parables to educate people into what they should desire. And most often, these parables situate technology as the solution.

Like all religious parables, these commercials put forward a concept of sin, intimations of the way to redemption, and a vision of Heaven. This will be obvious to those who have taken to heart the Parable of the Person with Rotten Breath, the Parable of the Stupid Investor, the Parable of the Lost Traveler’s Checks, the Parable of the Man Who Runs Through Airports, or most of the hundreds of others that are part of our youth’s religious education. In these parables, the root cause of evil is technological innocence, a failure to know the particulars of the beneficent accomplishments of industrial progress.

The god of Technology is an offspring of the narratives of Science and Progress. In fact, it equates human progress with technological progress. Technological progress is inevitable, as the story goes, and therefore we must fit ourselves into technology’s constraints, whatever those might happen to be. We must train students for this technological reality, whatever it is.

Woe to those who do not heed this god!

What does the narrative of Technology promise? According to Postman,

It [the narrative of Technology] demolishes the assertion of the Christian God that heaven is only a posthumous reward. It offers convenience, efficiency, and prosperity here and now; and it offers its benefits to all, the rich as well as the poor, as does the Christian God. But it goes much further. For it does not merely give comfort to the poor; it promises that through devotion to it the poor will become rich. Its record of achievement—there can be no doubt—has been formidable, in part because it is a demanding god, and is strictly monotheistic.

A bit further down Postman adds,

Those who are … inclined to take the name of the technology-god in vain, are condemned as reactionary renegades, especially when they speak of gods [narratives] of a different kind.

Postman’s argument, and one which I would agree with, is this: We need to learn how to think about technology. It is important to know how to use technology, yes. I’m very grateful for the man who taught me HTML in high school. Learning to use technology matters. But it’s not the most important thing.

We have to realize that technology giveth and technology taketh away, that there are winners and losers with any given technology. Technology simultaneously enhances and obsolesces aspects of human experience. Liberal arts colleges can serve as environments for interrogating the demands that technology makes on our lives. A liberal arts classroom ought to be a place for discussing and diagnosing the oftentimes taken for granted effects of technologies on our perceptions, institutions, and communal forms of life.

Like Postman, I’m not opposed to giving students useful skills. I want them to find a job and live a reasonably comfortable existence post graduation. I want them to be able to support themselves and their families.

But a liberal arts degree offers more than this—not less. School is a civilizing institution. It produces culture. It is more than a credential. It transforms your thoughts, your perceptions, your habits, and maybe even your morals.

The AI Death Blow

A word is in order about artificial intelligence. The Druid suggests that AI will deliver (or has delivered) the death blow to the liberal arts colleges that are merely limping along.

I'm not convinced that AI will destroy the liberal arts.

I am convinced that those who do not understand AI (LLMs, to be more accurate) and the purpose of the liberal arts will eventually capitulate to AI, destroying their very identity in the process.

Every technology tends to disrupt existing patterns of education. But that doesn’t mean education disappears. For the longest period of time, to be educated meant to know how to read and write. I think there are merits in learning to read and write at advanced levels, obviously. I’ve commented on what we lose with generative AI when it comes to writing.

However, in my estimation, we are entering an era where the spoken word will once again be ascendant in the academy, as it should be. LLMs retrieve the oral exam as a mode of testing knowledge. The close connection between speaking well and thinking well (and even acting well), the tie between eloquence and wisdom, once again has a chance to assert itself as it did in universities of old.

To those who would say AI seriously threatens the educational establishment, all I can do is cite a poem that Postman himself includes:

Mr. Edison says

That the radio will supplant the teacher.

Already one may learn languages by means

Of Victrola records.

The moving picture will visualize

What the radio fails to get across.

Teachers will be relegated to the backwoods.

With fore-horses,

And long-haired women;

Or, perhaps shown in museums.

Education will become a matter

Of pressing the button.

Perhaps I can get a position at the switchboard.An educator in the 1920s wrote this. Postman wryly comments:

I do not go as far back as the introduction of the radio and the Victrola, but I am old enough to remember when 16-millimeter film was to be the sure cure, then closed-circuit television, then 8-millimeter film, then teacherproof textbooks. Now computers.

Then he says, “I know a false god when I see one.”

I couldn’t agree more.

Why should I believe that? And so what?

Remember that despite their absolute necessity, narratives do not solve technical problems. Postman quotes Theodore Roszak:

Free human dialogue, wandering wherever the agility of the mind allows, lies at the heart of education. If teachers do not have the time, the incentive, or the wit to provide that; if students are too demoralized, bored, or distracted to muster the attention their teachers need of them, then that is the educational problem which has to be solved—and solved from inside the experience of the teachers and the students.

Educators would do well to regularly establish a purpose for their enterprise.

The death of the liberal arts is not an administrative problem. It is not an administrative problem because it is not a technical problem. Postman writes, “The problem, as I have been saying, is metaphysical in nature, not technical.” By metaphysical, he means the purpose or end of education.

Every teacher must ask, “What are we doing this for?” Education’s purpose simply cannot be taken for granted.

We must give students a reason for why they're doing what they're doing.

I had a mentor in grad school tell me early in my academic career that the two most important questions that you could ever possibly ask a teacher are:

1. Why should I believe that?

And

2. So what?

Unfortunately, you can’t get away with these questions in every classroom. But you will be encouraged to ask them (and others like them) in classrooms where teachers genuinely care about making you a more questioning, thoughtful human being.

The classroom needs a dialectical and rhetorical tension to keep it from disintegrating. These questions help establish that tension.

Every classroom needs a problem, an exigence, a reason for being. It needs less textbooks and more debate. It needs an edge to cut with. It needs a discussion early in the semester as to why we're doing what we're doing and the fact that we could always be spending our time otherwise.

It needs a regular injection of the outside world to keep it honest.

As Dorothy Sayers knew, the point of teaching students the liberal arts of grammar, rhetoric, and logic is to equip them to defend themselves beyond the walls of the academy. Now is as opportune a moment as ever for the liberal arts to be making sense of the rhetorical and political and technological developments going on all around us. As the word “liberal” in liberal arts suggests, the trivium of grammar, rhetoric, and logic are arts befitting of free persons.

Is the jig really up?

In this piece, I disagreed with Martin’s claim that all liberal arts colleges were zombies. On the contrary, the liberal arts have a unique contribution to make to the common culture. I suggested such institutions could survive if they understood the need for a common narrative. Moreover, I indicated that educators needed to be aware of the counter narratives at play: the gods of Economic Utility, Consumership, and Technology.

I leave it to you to decide not only whether the liberal arts are dead but also whether they ought to be dead.

There are some who prefer that young adults simply enter into the workplace, what Josef Pieper called “the world of total work.”

There are some who, despite their millions of dollars and despite their alienation, nevertheless insist that the liberal arts have nothing to offer. What could the liberal arts possibly teach us about living a meaningful life?

There are some who, having been in the trenches as a teacher and having seen the dire state of affairs in the liberal arts, have called it quits and condemned the whole endeavor as bankrupt.

Should we believe them? I don’t think so. I don’t think we have good reason to. But I do think we owe them a reply.

Justin Bonanno is an Assistant Professor with a PhD in Rhetoric. The preceding essay is his own opinion and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of his employer.

There have been several points throughout my final semester where I felt like putting my degree on pause. I no longer feel inspired, motivated, or any sense of meaning while performing such task as writing a discussion post, taking an online quiz, or learning business buzz words such as "sustainability" and the highly regarded "porters 5 competitive forces". Everyone I talk to says almost the same thing "you need the piece of paper to get in the door." What does this piece of paper display? "I can do something I don't want to do diligently for a long period of time." Is that how I want to live my life? To do things that have no perceived meaning or matter of importance. That sounds like bureaucratic hell.

I'm tired.