It’s a Tool, It’s a Medium… It’s a Bomb?

A Response to Roy and Stephenson on Our Metaphors for the Internet

I am writing this post as a response to the conversation between Substackers Helen Roy and Samantha Stephenson regarding the internet and how to use (or not use) it. I would like to add my own perspective to the debate because I think there is some unexplored territory to be discussed. I thank both writers for their articles and for their response to God’s call to write and raise questions, especially within the context of motherhood.

Roy’s piece, “The Medium is the Message,” began as a response to the killing of Charlie Kirk. She asks how a crisis of embodiment may be contributing to recent acts of violence as well as other “compulsive behaviors, be it physical abuse, binge eating, alcoholism, drugs, or promiscuity.”

Roy problematizes our excessive and obsessive internet use, which leads to a profound experience of disembodiment. This disembodiment has, for Roy, “become the default mode as our lives migrate more and more into the online spaces.” Here she cites our many compulsions to post and scroll, experiencing “all possible human emotions one after the other without pause, so much feeling, in fact, that you end up feeling nothing at all.” Then she offers the quote that gives her article its name:

If the medium is the message, the message is mass psychosis…we are poisoning ourselves and inviting others to poison us.

In choosing to name her article “The Medium is the Message,” Roy relates this “mass psychosis” to Kirk’s killing and modern man’s attempt to return to the body. Such acts of violence toward self and other attempt to “end the loneliness of disembodiment by performing an anti-sacrament: trying to incarnate the self by desecrating flesh, theirs or another’s.”

Roy defines embodiment as “a state of mind-body connection, a sense of mental presence in time and place, undistracted and unmediated.” For Roy, embodiment requires an appreciation of the physical, “local, vernacular, analog ways of doing life.” She claims embodiment as a particularly Catholic principle, citing our theology of an incarnate God and grace mediated through the physical realities in the sacraments of the Church. She also calls upon Pope Leo to offer an encyclical on proper use of technology in the context of a “digital revolution.”

While Roy offers some really interesting phenomenological thinking, she ends her article with this caveat:

To be clear, I love the internet. I don’t think Ludditism is the necessary answer to all this. One of the earliest lessons I have to teach each of my children is the difference between a tool and a toy. Scissors are good and useful. The internet is good and useful. Scissors are potentially, in fact very likely, harmful in the hands of a toddler.

She goes on,

I suppose the challenge is being able to recognize our own level of spiritual maturity, our ability to moderate our use of a highly addictive tool, and to know whether we are being tempted and to what.

It is particularly Roy’s assertion that the internet is a “tool” that I take issue with. The internet is much more than a tool, and it is quite possible that the response of the Luddite is warranted. Before explaining why, let’s first consider Stephenson’s article, “The Myth of Disembodiment: A Response to Helen Roy,” which appears as a guest post on Roy’s Substack under the title: “I was wrong(ish) about the internet.”

Stephenson’s main claim is this: “The ubiquitous metaphor of ‘disembodiment’ for our screen-based society is a fundamentally flawed framework. It isn’t that we leave our bodies behind when we immerse ourselves in the screen. It’s what we do to our bodies by living life online that’s killing us.”

Stephenson argues that because we are mind-body composites, disembodiment is the same as death. For her, we are not experiencing disembodiment but “an altered physiological state that produces a cascade of symptoms both physiological and emotional in nature.”

She goes on to describe the evils of the internet, but not before saying, “Roy and I agree that the tool that is the internet has enormous potential—for good and evil alike. The tools of the internet era are highly addictive because they’ve been engineered to be. They create a neurochemical reaction in the brain that triggers a behavioral addiction…We pull the lever and the chemicals rush in.”

Stephenson suggests that we “pull the opposite lever” by challenging the body, getting out in the sun, spending time in nature, and engaging in our communities. All wonderful suggestions. But Stephenson’s reminder that we attend to and care for our bodies does not do enough to answer the existential questions posed by our technology use.

For, though Stephenson is right that on a scientific level we don’t ever actually leave our bodies and do in fact harm them when we spend too much time online, Roy is right that phenomenologically we rend the body from the mind when we enter the online, digital space.

To be embodied is to be bound by time and space. For much of our history, messages could only move as fast as our bodies could travel (by foot, by horse, by train, etc.). With electric communication, we transcend the limits of the body. We communicate instantly. We travel across the world instantly.

So, what does this phenomenological experience do to our thoughts, our actions, our ways of educating people, our ways of raising children, or—as Roy points out in her posts about social media and motherhood—our ways of viewing our own vocational call? And how does our thinking of the internet as merely a tool limit our understanding of what is at stake?

Let’s go back to the beginning. Roy entitles her article, “The Medium is the Message.” But neither Roy nor Stephenson note the original source of this phrase: Marshall McLuhan. He was a Catholic and a Thomist. His famous phrases include “the medium is the message” and the “global village.” Reading McLuhan can be confusing and esoteric at times, perhaps because, like Louie Pasteur trying to convince his colleagues of the effects of unseen pathogens, McLuhan was trying to convince his contemporaries of the unseen effects of media on our forms of thought, culture, and education.1 Most of his work is oriented toward churning up the soil, probing for fresh insights, getting people to think beyond our taken-for-granted assumptions about what media are.

So, in the spirit of McLuhan, and with the help of Antón Barba-Kay, I hope to break up some of the simulacra preventing us from seeing digital media for what they are.

The Internet and the AI-Bomb

For Antón Barba-Kay, media connect us, and tools help us do things. Barba-Kay’s 2023 book A Web of Our Own Making argues that the recent transition to the reign of digital technology goes beyond other such transitions (i.e. silence to speaking, speaking to writing, and writing to printing) because it ushers in a new medium and a new tool (Web, 8). Digital technology combines knowledge with use, and not only does it combine the two, but it combines them on an infinite scale. Barba-Kay writes,

Unlike steam engines or wheels, it [digital tech] performs no particular task. Its usefulness stems rather from the fact that is can be used to measure, analyze, and reconceive all possible tasks. Its scope of action is, for this reason, completely unspecified and unrestricted. (Web, 7)

He goes on,

…it [digital tech] is as much a medium (a way of communicating) as it is a tool (a way of doing). Nor is it just one tool. Its versatility of purposes is so astounding as to make it a master tool. That is, it does not help us to perform just one specific task better (which is what most tools do), but it is the means by which any number of tasks are transacted… Aristotle called the hand the “tool of tools” (meaning: the tool by means of which all tools can come to be of service). But the hand is now getting a run for its money. (Web, 24)

For Barba-Kay, digital technology is not just a tool, but the “tool of tools,” containing all other tools within it.

Barba-Kay is careful to distinguish the internet from digital technology.2 Nevertheless, the internet is a form of digital technology. It doesn’t just help us communicate with one particular other on the other side of the world (as the telegraph did), but it connects us with everyone in the entire world at every possible moment. “To be connected to the network,” says Barba-Kay, “is to be everywhere in reach of everyone. To amend Marshall McLuhan: The connection is the message” (Web, 7).

Digital technologies like the internet combine the power of a tool of tools and a medium of maximum connectedness, and this makes them seismic in ways only comparable to the bomb (Web, 18).

For Barba-Kay,

Both [the internet and the bomb] are forms of maximum shared connection, of common destiny, purpose, or fate; they are the doomsday ends of our secular eschatology. The global village is manifest in bomb and internet: the bomb is the internet in body, the internet is the bomb in spirit…One of them represents oblivion; the other memorializes every human thought. The one is heat to incinerate suns; the other is light containing the world in thought. They are, taken together, the omega answering the alpha of creation. Both are machines for killing time, no wonder. (Web 19)

I want to make sure nobody missed this: The bomb is the internet in body, the internet is the bomb in spirit. If that doesn’t give us pause as human beings, as parents, and as Christians, I don’t know what will.

Tools vs. Environments

This brings me back to McLuhan. McLuhan is part of a tradition called media ecology, which, as the name suggests, studies media as environments. McLuhan was particularly incensed when people around him claimed that media are just neutral tools that can be used for good or for ill. He called this “the numb stance of the technological idiot.”

Neil Postman, another brilliant media ecologist, explains it this way in his book Technopoly:

Technological change is neither additive nor subtractive. It is ecological. I mean ‘ecological’ in the same sense as the word is used by environmental scientists. One significant change generates total change. If you remove the caterpillars from a given habitat, you are not left with the same habitat minus caterpillars; you have a new environment…This is how the ecology of media works as well. A new technology does not add or subtract something. It changes everything. (18)

A new technology ushers in a new world, a new service environment, new possibilities for communication and thought, new dynamics in relationships that never existed before. Postman writes,

New technologies alter the structure of our interests: the things we think about. They alter the character of our symbols: the things we think with. And they alter the nature of community: the arena in which thoughts develop. (Technopoly, 20)

Our new technologies change how we think, with whom we think, and what we think about.

I find this ecological metaphor extremely helpful for thinking through the various technologies we invite into our lives and our homes. Anyone who has ever worked in an office where management has decided to implement a new “tool” to increase efficiency knows that such tools often change everything. A new way of “punching in” for work may become a new source of anxiety, a new avenue for surveillance, a challenge to trust, an affront to an employee’s sense of agency, and the list goes on.

Take another example, one my mentor in grad school liked to give. The dishwasher enters the home where dishes used to be done by hand. Maybe it was installed to save the family time, to more efficiently deal with the piling dishes. Maybe that is exactly what it does. If we are thinking in terms of helpful or unhelpful tools, this might be where our analysis stops. You’re awesome, dishwasher!

But if we zoom out and view the dishwasher as an environment within an environment, we might notice that certain conversations no longer happen. You know, the ones where one person washes and another person dries? Similar to the disappearance of Postman’s caterpillars, the addition of a new technology has totally reoriented clean-up time and has disrupted a ritual that might have been integral to the family’s relational dynamic.

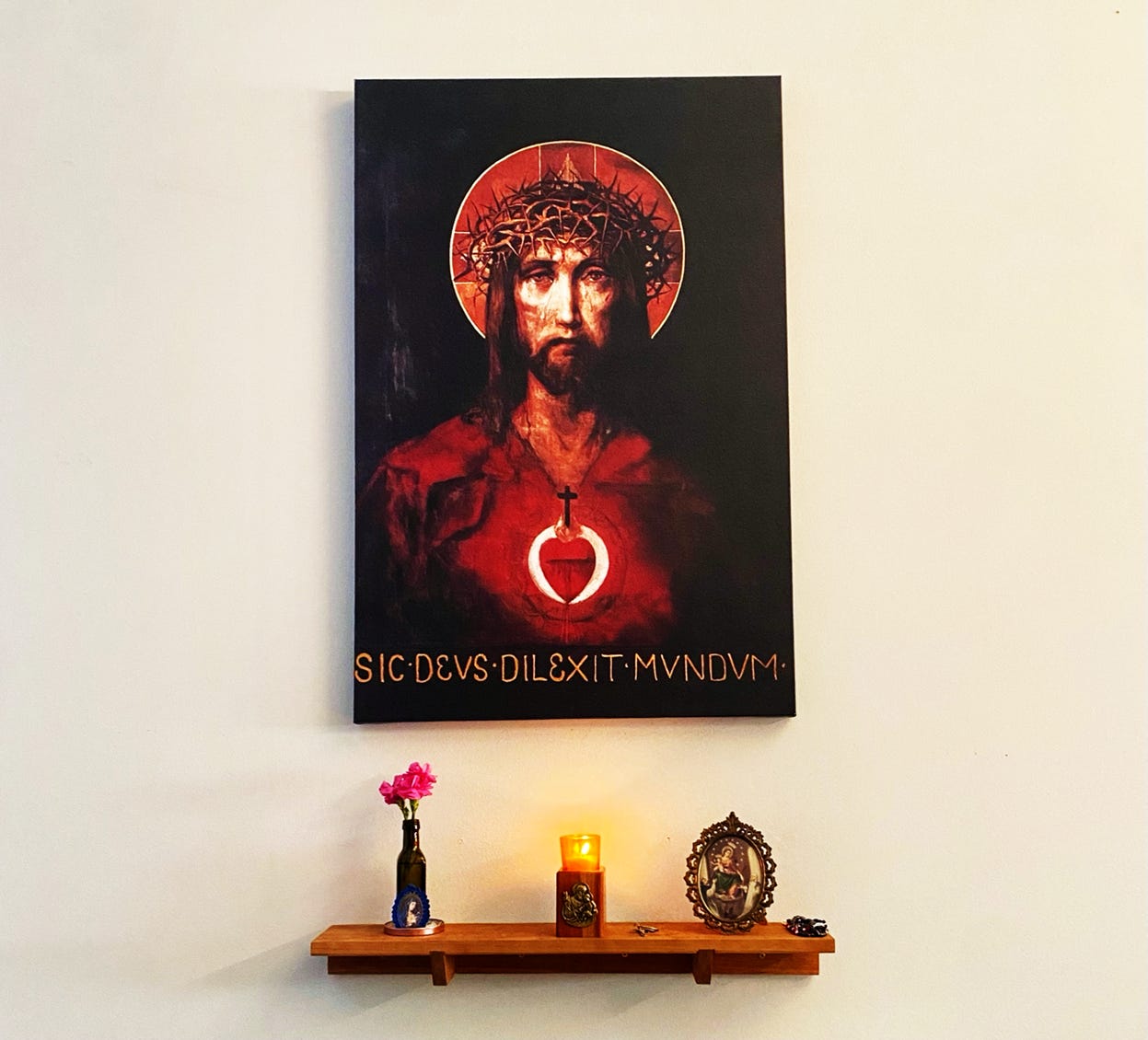

Finally, this example from my own life. We used to have a TV mounted on the wall, front and center in the middle of the living room. Underneath was a hutch to hold the DVD player, movies, and other tchotchkes. Now, both the TV and the hutch are gone, replaced by an image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, an altar, and a piano. If we think in environmental terms, we can see how each medium carries its own biases, constraints, and potentialities. These choices are not neutral. They encourage and discourage certain behaviors, certain ways of thinking. They open up new possibilities for a space, and they orient us as individuals, families, and cultures.

So, what is the point?

Our metaphors help us see things, but they also prevent us from seeing them. For Stephenson, Roy’s metaphor of disembodiment obscures the priceless role of the body in everything we do. I am personally troubled by the use of the term “tool” when it comes to the internet and the digital age in general.

When we call the internet a tool, we are invited to think of how it is like a pair of scissors, which can help us cut out intricate paper snowflakes or poke out our sibling’s eye. When we think of the internet as an environment, or even as a bomb, we can see how handing a toddler a phone is more like handing them the codes to a nuclear arsenal.

Roy does point to our responsibility as internet users “to know whether we are being tempted and to what.” In Cardinal Robert Sarah’s book The Power of Silence, Nicholas Diat and Sarah visit the abbot of the Grand Chartreuse to discuss silence. Here is what Dom Dysmas de Lassus had to say that has particular import for us and our families:

Temptations have multiplied; discernment and renunciation have become more necessary than ever…We have a cloister and a Rule that protects us. Someone who lives in the world must find his own cloister and his own rule; this is not something obvious! (Power of Silence, 229).

Those lucky chumps up there in the mountains get silence built into their vocations, they get a rule that protects them. We as men and women living in the world must create such spaces, must form a cloister and a rule of life for each of our families such that we do not get swept away with the tidal wave of information, mindless consumption, and foolishness that is characteristic of our culture and our time.

Media make us like themselves. They transform us as we use them, just as any other environment transforms us when we step into it (we become warm when we enter a warm room, we become like the friends we hang out with, etc.). If we really believe this to be true, then we can start to see our role as world-builders, not as tech optimists or Luddites.

We may not be able to set up shop in some ancient monastery, but we can make our homes domestic churches, beginning with what we want ourselves and our children to see, and hear, and touch, and taste there, and beginning with who we want them to become. For, as we know, we become what we behold.

Editor’s note: McLuhan compares himself to Pasteur in Understanding Media.

Barba-Kay writes, “‘Digital technology’ and the ‘internet’ are not interchangeable terms, though they are of course connected. What we do on our browser is the most obvious way in which we use digital technology, while the range of all digital sensors and their applications is much wider. A smart toaster, a digital camera, or a given software program is not ‘the internet,’ not as we would think of it; yet they generate digital data that may be uploaded, aggregated, analyzed, and controlled for online. By ‘digital technology’ I, [sic] therefore mean all kinds of measurement, programming, and processing that, by issuing standardized electronic information, may be integrated and exchanged within a single, widespread network” (6).

Excellent piece -- I've forwarded it on to quite a few folks!